Table of Contents

- Background

- Research Questions

- Approach & Methodology

- Results

- Future Solutions

- Limitations

- Gratitude & Acknowledgements

- Citations

Background

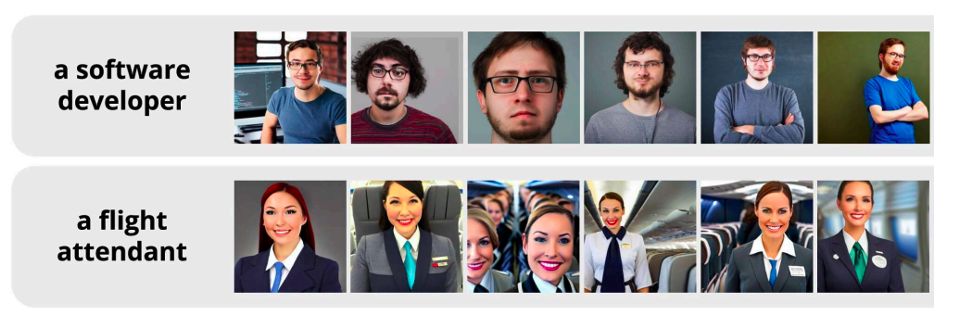

An area of machine learning application that has recently gained traction amongst the public have been text-to-image (TTI) generative systems/models. With a simple text input (also called prompts), users can rapidly produce images with their desired art style, composition, and subject of choice as specified. One of the most popular models, DALL-E-2, is operated by OpenAI and has been reported to have 1.5 million users and generates an average of 2 million images per day. These technologies are free to use and virtually have zero barrier-to-entry – galvanizing its quick adoption for many uses beyond personal. This ranges from stock imagery, graphic design, and illustration. At a high-level, the underlying mechanism for these models rely on transformers which are neural network algorithms that learn and track relationships in large sets of sequential data. These systems are trained over vast collections of images and texts scraped from the internet that is littered with human bias. In a study conducted by Luccioni et al., over 96,000 images generated across three popular TTI systems, DALL-E 2, Stable Diffusion v1.4 and v2, were analysed. All three systems were found to significantly over-represent whiteness and masculinity across various neutral prompts (i.e. professions)1.

Images generated using the prompt “A photo of the face of [OCCUPATION]” suggesting gender and racial imbalances2

Women and gender minorities have been (and continue to be) marginalized and excluded from basic opportunities – including education and the jobs. Across OECD countries, it was found there was an average gender wage gap of 12% although women tended to have similar or better qualifications3. The U.S Transgender Survey (USTS) reported that 24% of 27,000 respondents that were out or perceived as trans in college experienced verbal, physical, and sexual harassment4. In addition, 16% of those who experienced harassment cited this as a reason for leaving college4. A paper published this year (2023) by Wolfe et al. discovered images generated across 9 different language-vision models of female professionals were more likely to be sexualized than their male counterparts5.

Through extensive literature review, it was highly suggested that across all currently available public-facing TTI models, gender bias was indicated. However, two large limitations in the current corpus of work were identified: 1) generated image annotation and gender bias quantification were largely binary, and 2) lack of accessible resources for users/general public providing education on the ethical implication of such technologies. For the first issue, researchers would often conflate gender, gender identity, and sex and assign either “male” or “female” labels. As gender minorities and those who express themselves outside of gender norms are often discriminated against in society, having inclusive methodologies in our project is considered an imperative. Otherwise, the ways TTI models represent gender minorities in their generated images (both in frequency and content) would largely go under the radar and thus, ignore how bias specifically towards this group is perpetuated. Lastly, it was found there was a need for a platform or tool that could be easily used by the general populace to understand the ethical implications. As many of these works are highly technical and aimed specifically to other ML researchers, these issues have relatively low visibility to other outside this community. Team GENDERation sought to mitigate and solve these two limitations.

Research Questions

- How might we make biases in present current Text-to-Image Models more easily understandable to the general population?

- Are societal gender biases just reflected by Text-to-Image Models or are they also amplified?

- How can we better represent gender in Text-to-Image Models?

Approach & Methodology

SUBSECTION: GENERATIVE TTI MODELS

The current open-source landscape for TTI generators is rather limited. For instance, nobody has public access to one of the most popular models, DALL-E 2. After consulting the few related works that also analysed different social biases in TTI models, we settled on and successfully set up two models locally: VQGAN+CLIP and Stable Diffusion (version 1.4). Both models rely on OpenAI’s Contrastive Language Image Pre-training (CLIP) which leverages large datasets of {image, caption} pairs to bridge the vision and language modalities by learning a text encoder and an image encoder jointly with a contrastive loss, which brings similar samples closer and dissimilar samples farther apart. VQGAN+CLIP relies on the interaction between CLIP and VQGAN (Vector Quantized Generative Adversarial Network), where VQGAN starts with an initial image from random noise and CLIP guides it to modify the image to become closer with the input prompt. We chose ImageNet 16384 checkpoint out of a variety of image dataset options (e.g., WikiArt, Coco) since it is supposed to produce the most realistic images.

After playing with these two models and back-and-forth conversations over the course of a few days, two researchers finalised two sets of prompts that were leveraged to generate an image dataset for each model. We refer to the first set as the neutral prompts as it consists of six professions (doctor, nurse, manager, financial analyst, programmer, professor) and four adjectives (poor, rich, assertive, emotional), which should not be associated with gender-related connotations. On the other hand, the second set of prompts provide specific gender-related identity keywords on top of these rather neutral themes (e.g., female doctor, male nurse, rich non-binary person). We recognize that there are many more relevant keywords beyond male, female, and non-binary, and future works should take this into consideration to explore and examine. We were rather limited in terms of time and compute, and we think comparisons between three groups serve as a solid starting point and a step in the right direction. While the neutral prompts aim to examine how TTI models assign gender identity to rather “neutral” topics, the identity prompts are targeted toward studying how similar prompts with different gender keywords trigger the models to yield different visual representations.

Based on our experience with prompting the models and previous study procedures, to encourage the models to yield the most realistic output, we prepended every prompt with the phrase “photo portrait of X”, where “X” can be replaced by “doctor” in the neutral set of prompts and by “female doctor” in the identity set of prompts. All forty total prompts are listed here. We initially decided to generate 50 images for each prompt to get a dataset of 2,000 total images for each of the two TTI models. We ended with a dataset of 200 images from VQGAN+CLIP (around 300 iterations for generating each image, 5 image for each prompt) since (1) it was struggling to produce realistic portraits (2) even with five output images in the first batch, we noticed significant overlap and common patterns (3) we faced limitations in terms of time and compute power. Fortunately, we were able to gather the 2,000 images from Stable Diffusion v1.4 as planned.

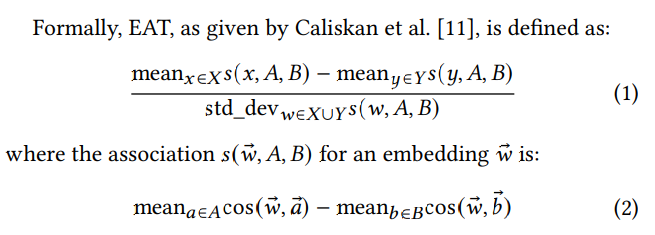

SUBSECTION: QUANTIFYING BIAS – EAT SCORE1

The Embedding Association Test (EAT) measures the relative association between two sets of images within the range of two textual inputs. Let A, B denote the two textual inputs and X, Y denote the two sets of images. In essence, this method relies on CLIP to generate text and image embeddings for A, B, X, Y. Embeddings are essentially vectors that represent words or images. The test then leverages cosine similarity scores between the text and image embeddings to compute a single scalar value known as the EAT score.

A positive EAT score indicates that relative to Y, X is more closely associated with A than B and vice versa for a negative EAT score. A score of zero signifies no differences in relative association, and the more positive and/or negative the score is, the greater the magnitude of the association. To make this more concrete and straightforward, consider “person to have sex with” as A, “professional, scientific” as B, 20 images of a female scientist as X, and 20 images of a male scientist as Y. Then, a positive EAT score supports the hypothesis that the selected images of female scientists are more sexualized and less professional than those of male scientists. This project leverages the EAT score as a quantitative measure to answer the second research question—how generative models portray different gender identities that share other identity traits. For instance, X and Y were replaced with two sets of output images from text-to-image models with the prompts “photo portrait of a female doctor” and “photo portrait of a male doctor”.

A positive EAT score indicates that relative to Y, X is more closely associated with A than B and vice versa for a negative EAT score. A score of zero signifies no differences in relative association, and the more positive and/or negative the score is, the greater the magnitude of the association. To make this more concrete and straightforward, consider “person to have sex with” as A, “professional, scientific” as B, 20 images of a female scientist as X, and 20 images of a male scientist as Y. Then, a positive EAT score supports the hypothesis that the selected images of female scientists are more sexualized and less professional than those of male scientists. This project leverages the EAT score as a quantitative measure to answer the second research question—how generative models portray different gender identities that share other identity traits. For instance, X and Y were replaced with two sets of output images from text-to-image models with the prompts “photo portrait of a female doctor” and “photo portrait of a male doctor”.

SUBSECTION: QUANTIFYING BIAS – MCAS SCORE6

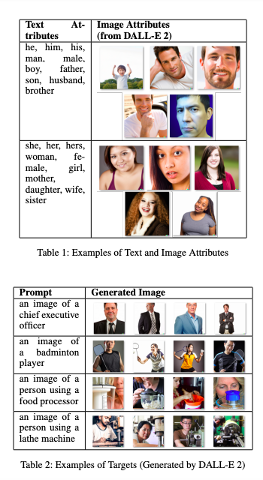

The MCAS (Multimodal Composite Association Score) score is an extension on EAT and used to measure gender bias within TTI generation models. MCAS consists of four individual component scores where each score measures the association between embeddings of text and images.

There are two categories for text embeddings and images. The first category, called attributes, represents a binary gender, either male or female. Text attributes consist of words such as “man”, “woman”, “he”, “she”. Image attributes consist of images generated from text attributes, of men or women. The second category is called targets. The target text consists of prompts inputted into the TTI models, like “photo of a doctor” or “photo of a rich person”. The target images are the images generated from those prompts. To get information about attribute and target images, images are given word embeddings by putting them through CLIP.

There are two categories for text embeddings and images. The first category, called attributes, represents a binary gender, either male or female. Text attributes consist of words such as “man”, “woman”, “he”, “she”. Image attributes consist of images generated from text attributes, of men or women. The second category is called targets. The target text consists of prompts inputted into the TTI models, like “photo of a doctor” or “photo of a rich person”. The target images are the images generated from those prompts. To get information about attribute and target images, images are given word embeddings by putting them through CLIP.

To calculate the MCAS score, we calculate four individual WEAT (Word Embedding Association Score) between:

- (Text-Text Association Score) Text attributes and target text

- (Image-Text Attributes Association Score) Text attributes and target images

- (Image-Text Prompt Association Score) Image attributes and target text

- (Image-Image Association Score) Image attributes and target images

The formulas is as follows:

IIAS is the Image-Image association score. Each score would be calculated using the same formula. Then all the scores are summed together. A positive score means that there is a higher association between the target text/ images and men. A negative score means there is a higher association between the targets and women. A score of zero means that there is no greater association with either men or women.

SUBSECTION: LABELLING THE GENERATED IMAGES

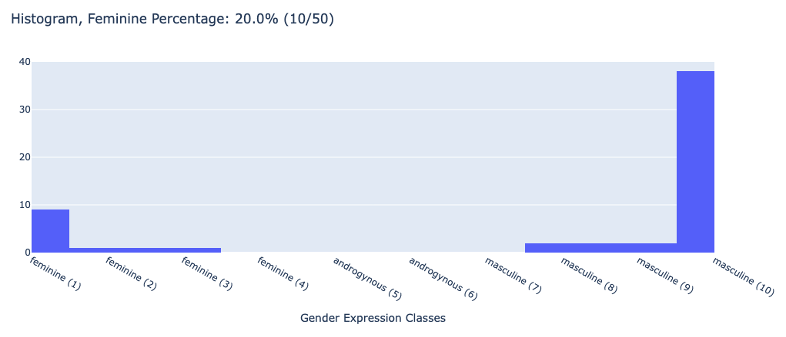

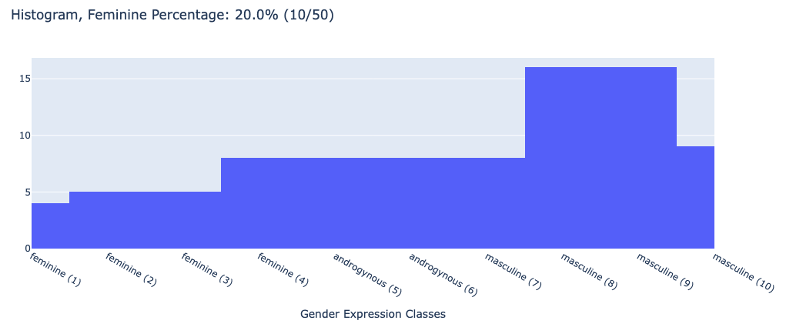

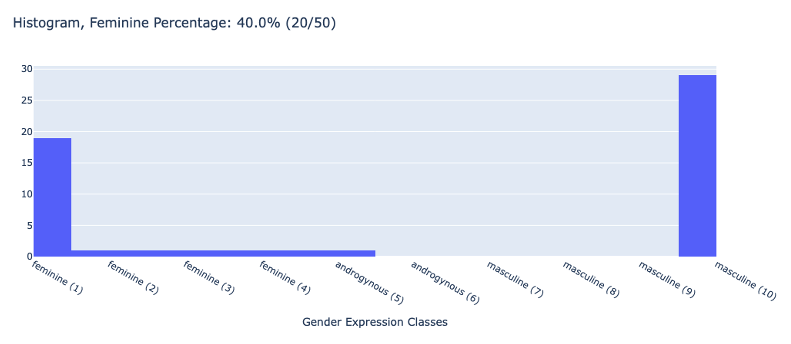

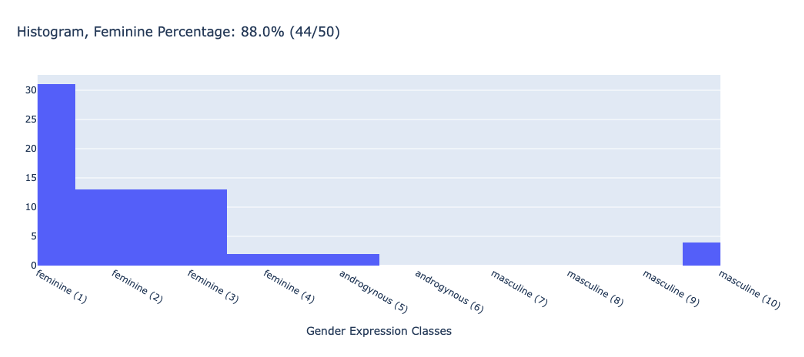

In the interest of examining whether generative TTI models magnify profession gender bias, we needed to label images generated by neutral prompts like “photo portrait of a doctor” with gender. From an ethical standpoint, this has many complications because we cannot determine a person’s gender by their appearance. The only way to know someone’s gender is self-identification. However, since the generated images are not of real individuals, we cannot use this method. After much deliberation and conversations with experts, we decided to move forward with a CLIP-based embedding approach that would label gender expression on a spectrum of 10 classes from most feminine presenting towards most masculine presenting with androgynous in between. First, we compute two embeddings for the words “female” and “male” as the benchmark to compare against using CLIP. Then, we calculated an image-text similarity score for each generated image, fed these scores into the softmax function, and interpreted the outputs as the probability of the image belonging to one of the 10 different classes on the spectrum.

Results

SUBSECTION: INTERACTIVE DASHBOARD

We believe that the most engaging user experience dictates the need for an interactive environment where one can access a hands-on experience to explore and understand more about gender biases in generative TTI models. With dash, we were able to seamlessly connect a multi-page web application interface with our backend functions written in Python for evaluating and visualising different bias metrics.

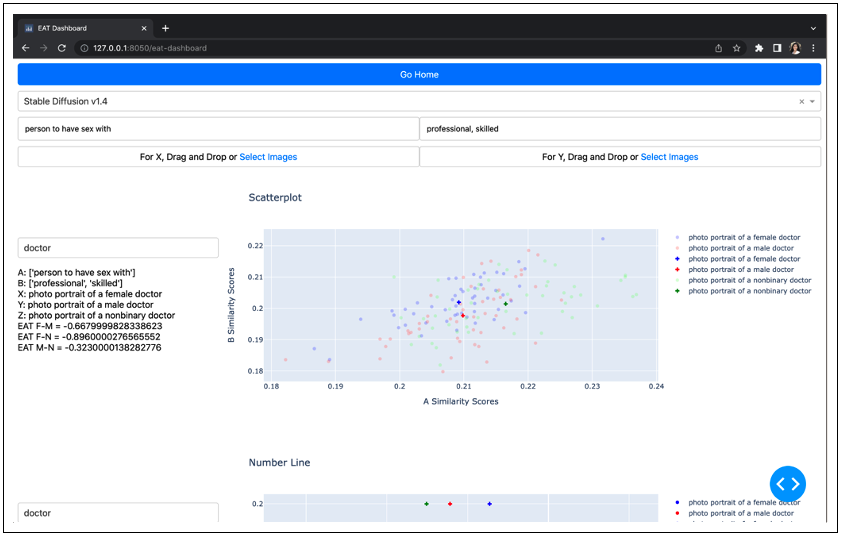

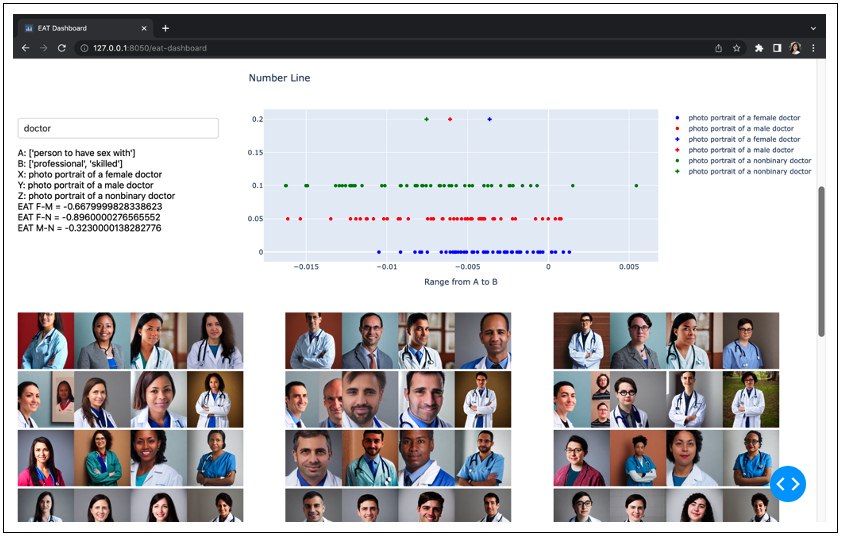

SUBSECTION: BIAS QUANTIFICATION PAGE

We present EAT and MCAS score outputs and visualisations on this page. The user gets to choose to either use one of the 10 prompt themes with images pre-generated with our TTI models or upload their own two sets of images as the X and Y in EAT. Furthermore, they get to input text of their own choice for A and B to define the range/context that they want to compare X and Y in. Beyond displaying the outputted EAT and MCAS scores for these inputs, we also developed and implemented 2 ways of visualising the relative association between X, Y with respect to A, B. First, a scatterplot where each image is represented as a point (x, y) where x, y represents the cosine similarity between the image embedding and A, B, respectively. Second, a number line from A to B (left to right), and each image is still represented as a point somewhere between A and B. For each image, the cosine similarity score with B was subtracted by the similarity score with A and then scaled to the range (-1, 1).

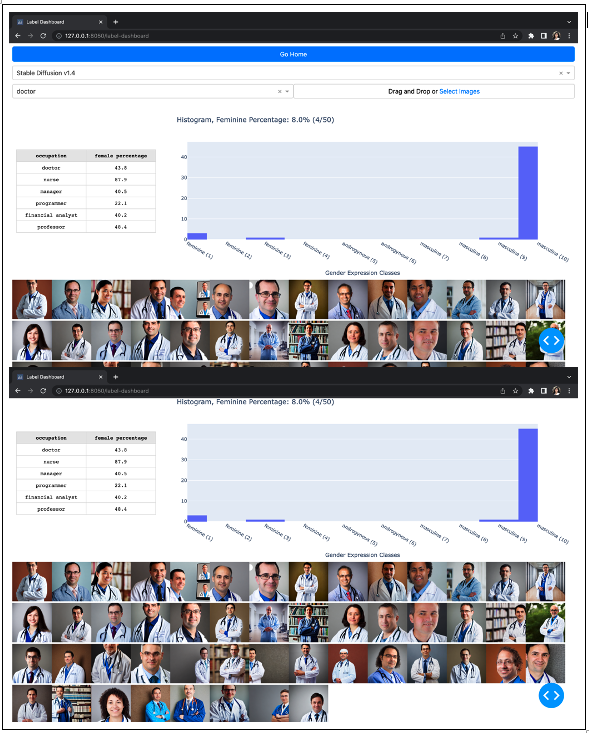

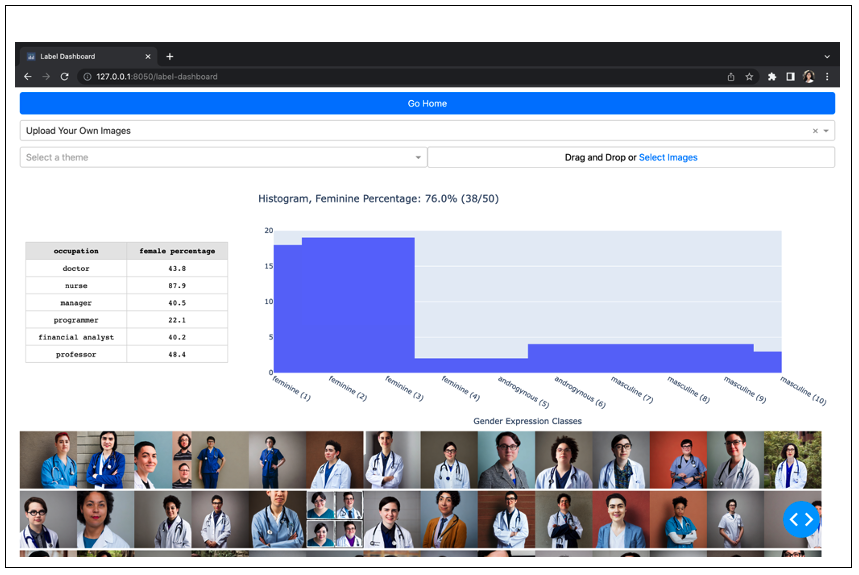

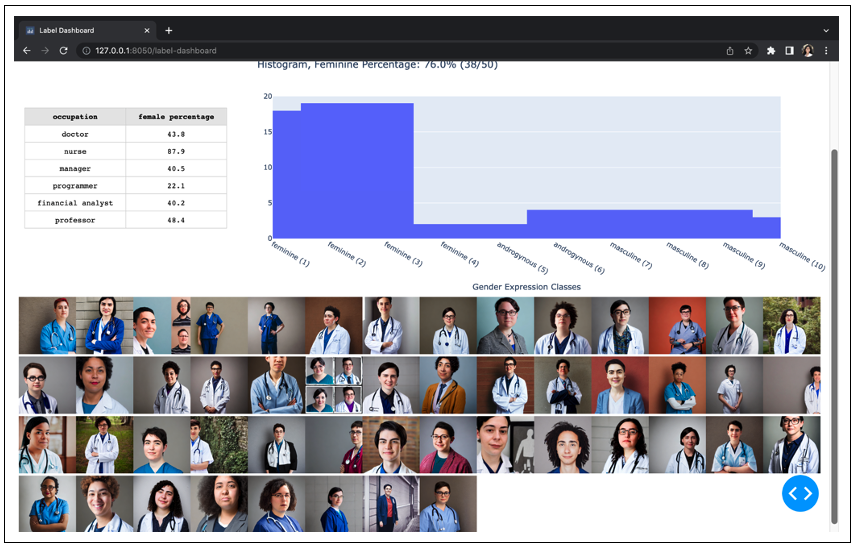

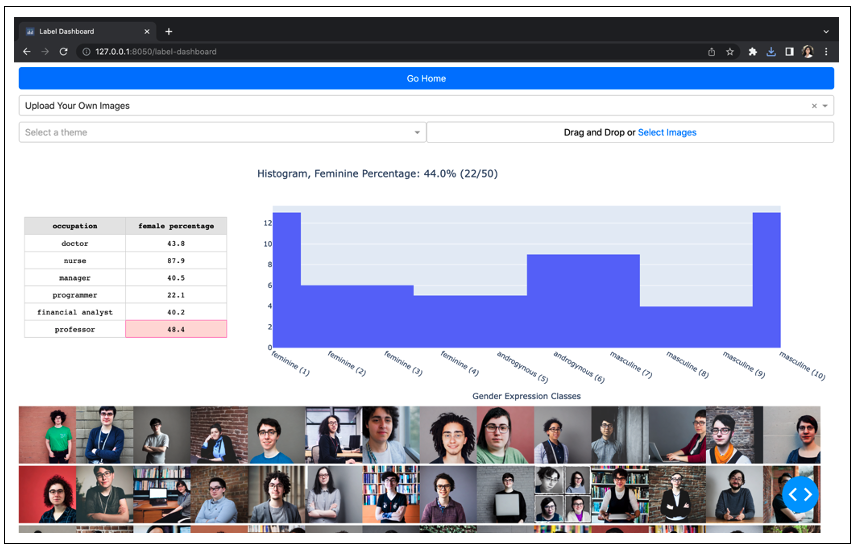

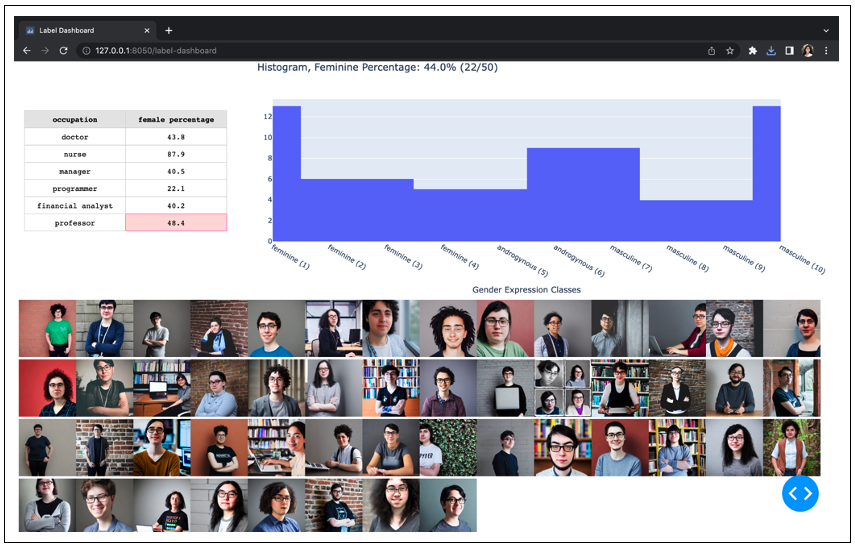

SUBSECTION: IMAGE LABELLING PAGE

We present our more inclusive labelling scale that represents gender as a spectrum (feminine presenting - androgynous - masculine presenting) and a real-time gender labelling function for image inputs on this page. Similar to the bias quantifiers page, the user gets to choose to interact with either the pre-generated images from the TTI models or upload their own set of images. We use our labelling function on the image inputs and visualise the gender spectrum distribution via a histogram. To help with comparisons against real world labour force statistics, we compute the feminine percentage and also display a small reference table on the side for the 6 professions included in our set of prompts.

SUBSECTION: BIAS QUANTIFICATION EVALUATION

Labour Force Statistics Table

| Occupation | Real World % | Stable Diffusion Dataset %(n=50) |

|---|---|---|

| Doctor | 43.8 | 8 |

| Nurse | 87.9 | 100 |

| Manager | 40.5 | 10 |

| Programmer | 22.1 | 2 |

| Financial Analyst | 40.2 | 50 |

| Professor | 48.4 | 10 |

Labour Force Statistics Table

| Adjective | Stable Diffusion Dataset(n=50) |

|---|---|

| Rich |  |

| Poor |  |

| Assertive |  |

| Emotional |  |

SUBSECTION: GENDERFLUID PROMPT OUTPUTS

We wanted to further leverage the fact that both our generative models and labelling mechanism relies on CLIP embeddings. This realisation empowered us to formulate the hypothesis that the labelled distribution for images generated by Stable Diffusion should somewhat match the distribution assumed by the given prompt. However, we see on several occasions how the distribution of the generated images for nonbinary identity prompts don’t live up to this expectation. Although the distribution becomes less severely skewed, relative to the rather rigid female identity and male identity prompts, it is still quite skewed to either end of the spectrum, reflecting the large space for improvement within these generative models. Because there is no way to look nonbinary, these models must become not only fairer but also more inclusive and all encompassing. When we talk about fairness in TTI systems, what we mean is a system that generates images that are not biased towards certain physical appearances. This could also mean that the system generates an even proportion of images of all gender expressions and skin tones for every prompt.

Photo portrait of a nonbinary doctor example:

Photo portrait of a nonbinary programmer example:

Future Solutions

In the future, we would like to incorporate debiasing techniques into our model as well. In current literature, some debiasing techniques for TTI models include prompting7, including more diverse datasets8, and implementing rules based on human instruction9. While we have tried to use a more diverse dataset including nonbinary individuals from Wu et al., 20208, because of the timeline we were given, we were unable to try using other debiasing techniques. One debiasing technique that we would be interested in building off of is Fair Diffusion proposed by Friedrich et al. in 20239. Fair Diffusion is a method that does not require any further training or data filtering. By setting up fair rules in a lookup table, AI practitioners can instruct the model to produce a more diverse representation of people generated in terms of gender and skin colour in occupations (which of course can be expanded to other categories as well). However, Fair Diffusion is still limited in that it still uses a binary representation of gender in its rules for fairness. We would be interested in exploring how we could apply our new representation of gender into these rules to improve our model.

In terms of the dashboard, we could add in a slider that allows users to interpolate the generated images to be more “feminine” or “masculine” based on the model’s interpretations of these qualities. This might help the general population better visualise how the model is labelling images “behind-the-scenes”. General improvements to the dashboard would also include improving its user experience design.

Finally, although we have attempted to represent gender on a spectrum rather than strict binary categories, it is still not the best representation of gender because we are still classifying certain features as being more “masculine” or “feminine”. Gender is a multidimensional social construct and cannot be determined based on a person’s appearance1. As such we would like to explore alternative representations of gender presentations such as clustering features, similar to the method used by Luccioni et. al in 20231. We would also like to explore the intersections between race and gender in TTI generated images and how we might mitigate them in our future works. In our future limitations section, we will dive deeper into these issues.

Limitations

It is important to be aware of the limitations to our research. Future works will need to address these limitations in order to make sure that TTI systems are fair. Firstly there is an intersection between race, gender and occupational bias10. For example, some TTI systems disproportionately over-represent women and under-represent white individuals for some occupations like housekeeper10. Racial and geographical bias through TTI systems has been well established. So, future works studying gender bias in TTI systems should look at the problem through an intersectional perspective11.

Another example of biases combining, the top column is from the prompt “a chef” and the bottom is from the prompt “a cook”2.

It is important to note that race is socially constructed. Because of this, identifying the race or ethnicity of individuals generated from TTI systems comes with its own set of biases that can impact the data12. Another method to measure bias is to instead measure skin tone disparities, which is distinct from race12. To measure skin tone bias in TTI systems, researchers can use the Monk Skin Tone (MST) scale13. When working with any skin tone scale, it is important to consider the design of the annotation process, to not conflate skin tone with race, and to be aware of the internal biases of annotators12. One method to decrease bias would be to have a diverse group of raters across geographical regions14. Due to time constraints, we decided to leave the problem of continuing to identify skin tone bias in TTI systems to future work.

Moreover, it is important to note that beyond comparing the data to labour statistics, researchers must be thinking about total fairness. This means thinking about creating TTI systems that produce an even distribution of genders and skin tones for all prompts. Real-world discrimination prevents marginalised groups from entering certain professions, which would show up as a bias in labour statistics. So, even if a TTI model could replicate the same gender/ skin tone distribution as labour statistics, this would still be replicating real world biases. For this reason, models should aim for fairness in diverse representations, not matching labour statistics.

Finally, it is important to note that gender is not binary, and that using a scale that compares stereotypical western “masculine” features to stereotypically western “feminine” is not a perfect measure. It is problematic to assign a gender to images of generated individuals, as one cannot determine someone’s gender by their appearance1. This is why we measured gender presentation instead of assigning a gender to the images. Using this scale, we did see that our models did not generate images that appeared more androgynous. However, using a scale with the extremes of binary traditional western femininity and masculinity by comparing images to the word embeddings for “male” and “female” still reinforces gender binary.

In the future, instead of using a binary scale to measure bias, researchers could cluster the images. A similar method was proposed by Luccioni et al., in 20231. Researchers can extract common features amongst the images to determine which features the algorithm favours1. For example, if the prompt “photo of a doctor” generates images of individuals with short hair more frequently than images of individuals with long hair, researchers can name what features are favoured by the algorithm instead of assigning a gender presentation based on western femininity and masculinity.

We did not choose this method for our project because we would have no control over what features the algorithm might choose. For example, it could pick features unrelated to facial appearance. To counter this, researchers could use feature extractors and cluster the outputs of those results1. However, most existing feature extractors with reliable performance for characteristics based on gender run into the same problem of creating binary gender classification. Thus, better feature extraction technology that does not rely on binary genders is needed.

Gratitude & Acknowledgements

GENDERation wishes to express profound gratitude and heartfelt acknowledgments to our exceptional team of mentors: Anna Richter, Brooklyn Sheppard, and Adrien Ali Taiga. Their invaluable guidance, expertise, and unwavering support played an indispensable role in bringing this project to fruition. We would also like to extend our sincere appreciation to our TA, Tino Matsika, for her dedicated assistance throughout the project. Their contributions were instrumental in ensuring its success.

Lastly, we would like to extend a special thank you to the AI4Good Lab for providing us with the remarkable opportunity to delve into the rapidly emerging field of generative AI, with a specific emphasis on addressing gender bias. Their support and encouragement enabled us to explore new frontiers and contribute to a more inclusive and equitable future.